Leisure • Self-Knowledge • Art/Architecture • Fulfilment

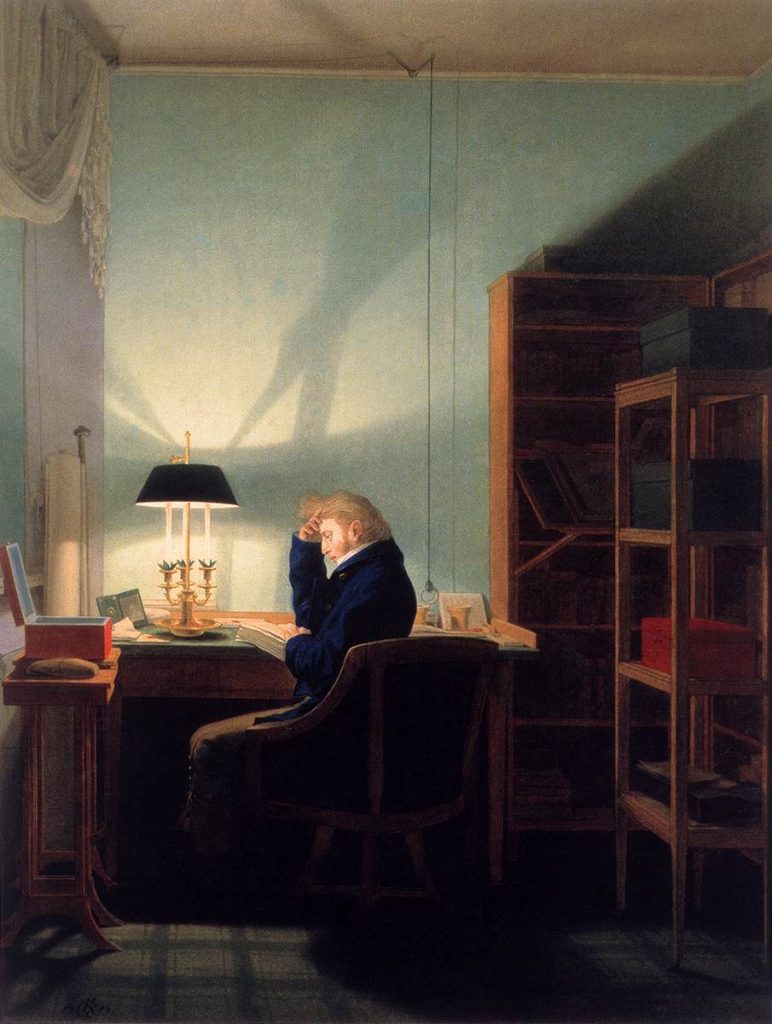

On the Consolations of Home | Georg Friedrich Kersting

We might be tempted to feel rather sorry for someone who confessed that their greatest pleasure in life was staying at home — or, yet worse, that their deepest satisfactions sprang from interior design. What would need to have gone wrong for someone to prefer their own bedroom or kitchen to the theatres and clubs, parties and conference venues of the world? How narrow would someone’s horizons need to have grown for them to devote hours to choosing a flower-ringed vase for the sideboard or a brass lamp for the study? Our era has a hard time maintaining sympathy for domesticity. Reality lies outside our doors. There are really only two categories of people who can be forgiven for being heavily invested in staying at home: small children — and losers.

But after launching our ambitions on the high seas, after trying for a few decades to make a mark on our times, after exhausting ourselves sucking up to those in power and coping with gossip, slander and scandal, we might start to think less harshly of those who prefer to remain within their own walls and think a lot — and with pride — about cushions and jugs, pencil pots and garlic crushers, laundry cupboards and cleaning products.

It might, of course, be preferable to manage to bend the world to one’s own will, to tidy up the minds of millions or to fashion a business in one’s image, but after a bit of time on the planet, some of us may be ready to look with new understanding and admiration at those who can draw satisfaction from making blackberry jam, planting beds of lavender or waxing bedroom floors.

The painter Georg Friedrich Kersting was born in northern Germany in 1785 and as a young man, wanted to become a great military general and perform heroic deeds in battle. He dreamt of helping to expel the French armies, which under Napoleon occupied large areas of the German states. After briefly studying art in Copenhagen, Kersting joined the Lützow Free Corps, a Prussian volunteer force, and saw action at the Battle of the Göhrde, in which thousands lost their lives and where he received the Iron Cross for bravery.

But after the defeat of Napoleon, during the political impasse that befell the German states, something changed in Kersting. He retired from the military, gave up on politics, moved to Dresden, got married, had some children — and got very interested in the idea of home.

He had had enough of machinations in government and the schemes of generals, of German nationalism and wars of liberation. Such ventures and the ideals that supported them became bound up in his mind with hubris and overreach. He was haunted by the bloodletting that he had witnessed and the friends from the military he had lost. From now on, what would interest him was the challenge of leading a good enough ordinary life in domestic circumstances and of remaining sane and serene when there was so much that might unbalance and perturb one. He closed the door on the world, and became a prophet of the consolations and beauty of home.

In 1817, Kersting completed one of the most quietly remarkable and beguiling of all paintings. The Embroiderer shows a young woman in a dignified modest dress absorbed in her work at an open window. One cannot see her face, but one imagines her lips pursed in concentration, her little finger on her right hand extended and taut from the effort of threading her needle. The interior is peaceful and inviting, without being in any way showy or extravagant. Someone has thought hard about how the mauve sofa will create an intriguing contrast with the green wallpaper and the chunky wooden floor boards have been matched up with an especially graceful chair and table, suggesting a reconciliation between practicality and elegance.

A few years later, Kersting completed an equally iconic companion piece. This time it is night and a woman is again at work doing some darning. A lamp has been swung into place and the room is bathed in a soft light; soon it will be time to make some camomile tea, kiss somebody on the forehead and rearrange their teddy and then, gradually, go to bed. The task isn’t distinguished or obviously memorable, there will be no government medals or honours handed out as thanks for it, but through Kersting’s eyes, we’re in no doubt that something very special is going on. The sitter has been cast as a secular saint of a new home-focused creed which rejects prevailing assumptions about where glory might lie and what must count as intelligent and purposeful. Perhaps those who focus on home will not gain distinction or renown, their graves will not commemorate any obviously glittering deed but they will nevertheless have played a role in supporting civilisation. It is to misunderstand where satisfaction lies to insist that fulfilment can only exist in cabinet rooms and boardrooms, stock markets and opera houses; the more imaginative will know the distinctive pleasures of preparing a family meal or painting a room, hanging a new picture or filling a vase with hyacinths and lilies of the valley.

We might once have wanted to tame and educate the entire world, to have had millions of people agree with us and to gain the adulation of strangers. But such plans are inherently unstable and open to being destroyed by envy and vanity. We should gain security from knowing how much a devotion to home can shore up our moods if our wider surroundings grow hostile. When we have become a laughing stock, when no one wants to know us any more, we can reactivate our dormant appreciation of our surroundings and find meaning in nothing greater or smaller than sewing on a few buttons in the late evening or choosing a new fabric for a chair. Kersting was not naive, he understood how war, politics and business worked, but it was precisely because he did so that he was keen to throw his spotlight elsewhere. His art was — in the deep sense — political, in that it articulated a vision of how one should ideally live: it covertly criticised military generals and emperors, business leaders and actors. It told us that waving flags at rallies and sounding important at meetings was well and good, but that the true battles were really elsewhere, in the trials of ordinary existence, and that what counted as a proper victory was an ability to remain calm in the face of provocation, not to despair, not to give way to bitterness, to vanquish paranoia, to decode one’s own mind and to pay due attention to passing moments of grace.

Kersting spent much time in his own study, which he represented in a number of sketches and one especially famous painting. He must sometimes have regretted his old ambitions. It must have hurt that he never made a fortune and that he remained, in his life time, relatively undiscovered. There might have been days when he felt that he had made all the wrong choices.

Nevertheless, his art continues to be a point of reference for those who have had enough of trying to bring order to the public square. It urges us to accept the consolation and peace available in ceasing to worry what others think and of learning to limit our ambitions to the boundaries of our own dwellings and laundry cupboards.

Tonight, we might — once more — choose to stay in, do some reading, finish patching a hole in a cardigan, try a new place for the armchair and be intensely grateful that we have overcome the wish to live too much in the minds of strangers.