Leisure • Self-Knowledge • Psychotherapy

Why You Should Take a Sentence Completion Test

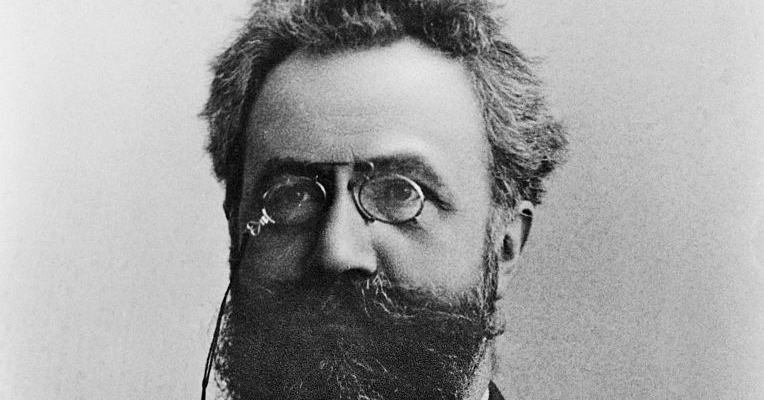

An urgent task of psychology is to devise tools that, rather like the claw crackers and spatulas served up in lobster restaurants, will grant us better access to the fruitful and salient bits of our own thinking. We should, in this regard, be especially grateful to a once world-famous, now largely forgotten nineteenth century German professor of psychology Hermann Ebbinghaus.

Born into a wealthy merchant’s family in Barmen on the Rhine in 1850, Ebbinghaus was a brilliant student from a young age and by his early 20s, set out to explore through original research the paradoxes and secrets of mental functioning. He was especially interested in memory and in 1885 made his name with a book called Über das Gedächtnis (“On Memory”), in which he named and described what we still refer to today as both the Learning Curve and the Forgetting Curve; models of the way in which information is absorbed, held and dispensed of by the mind over time. The professor also discovered what is now known as the Ebbinghaus illusion; a way of demonstrating that we judge the significance of things not in the abstract but in relation to what is most immediately near to them, an idea with wide application in psychology, for example in the way we judge our status or the severity of a setback.

Most importantly for us, it was both in this book and in a follow-up Fundamentals of Psychology, published in 1902, that Ebbinghaus devised a test that was to change how we are able to extract our identities from our personalities. This test, at once very simple and completely revolutionary, is known to us now as the Sentence Completion Test. Ebbinghaus discovered that one could hugely improve one’s level of self-understanding by completing broad sentences about one’s feelings or desires, without straining or thinking too much when responding. Examples of such questions include: What I really want is… Or: My biggest regret is… Or: What I really want to change about myself is…

Day to day, it is as though shyness or fateful distraction keeps us away from grasping these fundamentals about ourselves — perhaps for fear of upsetting the mental status quo, given that our answers are on occasion starkly in conflict with the respectable or desirable position on things. Ebbinghaus wisely observed this in relation to two incomplete sentences in particular: The person I really love is… and: If no one ever found out, I would love to…

Here a married high court judge might answer ‘the coachman’ and ‘be flogged while wearing my lawyer’s gown.’ An advocate of left-wing causes might respond: ‘the queen…’ and ‘live in luxury.’

The extent to which we hide ourselves from ourselves has, since, become well known in psychoanalysis but what makes Ebbinghaus’s Sentence Completion Tests so compelling is the speed and relative simplicity with which our defence mechanisms can be bypassed and information extracted. A truth that might have required twenty sessions of therapy to emerge in tentative confusion might shoot come out of someone with nothing more outwardly complicated or costly than a question on a sheet of paper like: What I’m really sad about is…

Ebbinghaus did not properly capitalise on his brilliant invention. This needed to wait half a century until, in 1950, the American psychologist Julian Rotter of the University of Connecticut published what he called the RISB — Rotter Incomplete Sentences Blank. Designed for three different audiences — the under twelves, high school students and adults — Rotter’s test asked recipients forty questions, including these taken from a test he ran with an adult male:

I like… to be with people I feel comfortable with.

The happiest time… I had was in high school.

I regret… that I have changed.

The best… thing in the world is love.

People… are good as a whole.

I can’t… play basketball very well.

I suffer… from getting too excited all the time.

Rotter’s test has become a mainstay of academic psychologists who have surrounded it with considerable and arguably rather unhelpful complexity. Standard operating rules suggests that one needs a PhD and six months of specialist training to interpret the answers; the manual that accompanies the test runs to 300 dense pages.

But fortunately for us, the most vital parts of the truth about who we are readily available to us to see rather clearly the moment we finish any Sentence Completion. We don’t need a PhD to understand what is going on when we answer:

I would love…

or

I am scared…

Ebbinghaus’s invention has spawned what is perhaps the grandest and most condensed of all completion tests:

I am…

People are…

Best of all, each of us is our own most accomplished and wisest designers of tests, because we all have a good sense of what we are concealing from ourselves. All we need to do to make major progress in self-understanding is to follow Ebbinghaus and set ourselves some tests under large categories like Love, Career and Family.

Central truths about who we are waiting to be known, just one unfinished sentence away.